Northern Ont. trappers opposed to new federal protections for unique wolf species

A unique wolf species in northeastern Ontario is getting more protection from the federal government, but not everyone is happy about it.

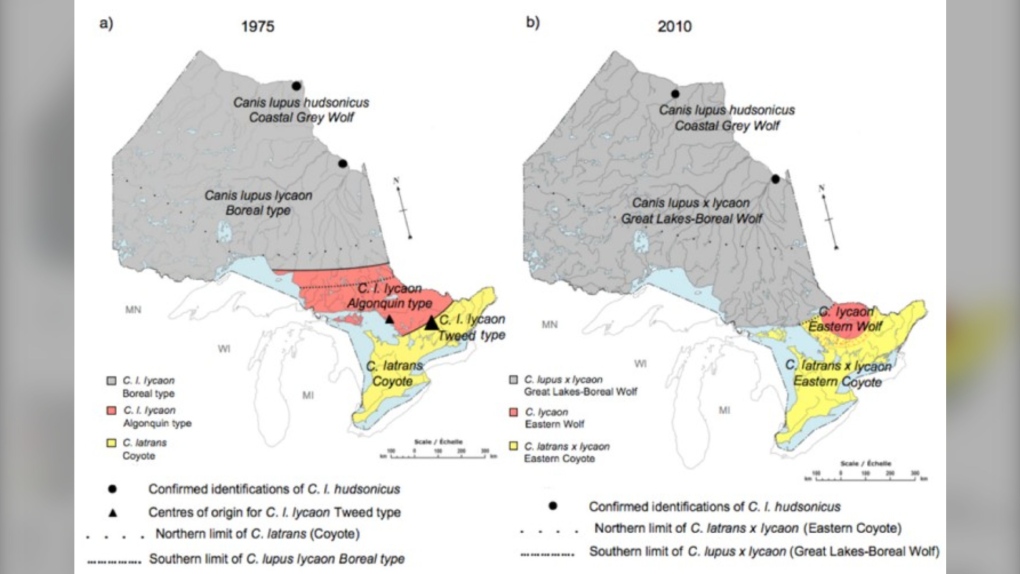

The eastern wolf, also known as the Algonquin wolf, has been recognized as a distinct wildlife species.

Interestingly, the species was originally thought to be a subspecies of the grey wolf that is common in the north but is actually more connected to the endangered red wolf of South Carolina.

Described as "one of the most elusive at-risk carnivores" by the Nature Conservancy of Canada, the eastern wolf was first deemed threatened by the province eight years ago.

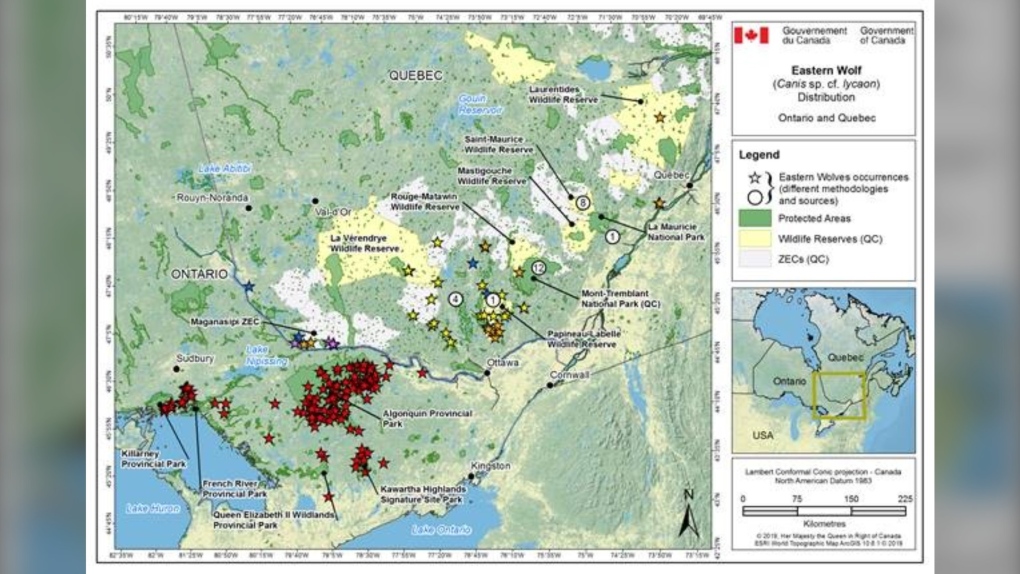

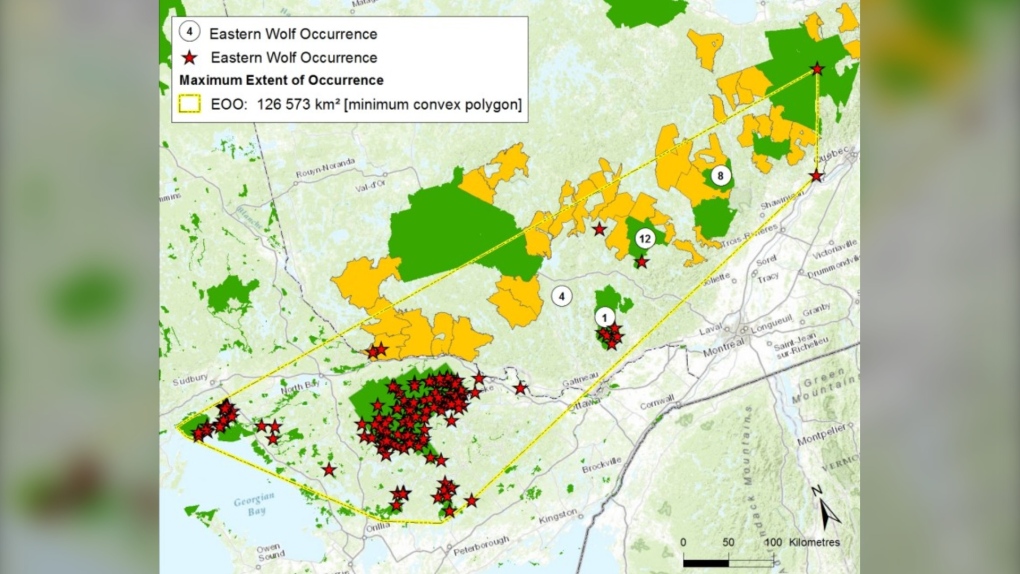

The mottled brown canine is found in the forests of the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence regions of Quebec and Ontario.

Former Ontario environmental commissioner Gord Miller is the chair of a grassroots conservation group called Earthroots that is dedicated to wilderness protection.

Miller said the eastern wolf is a unique species that has been in North America for a very long time and the predator is a keystone species in its habitat.

"It is a threatened species because it is limited in numbers – to less than 1,000 – and it's limited in area that it occupies," he told CTVNewsNorthernOntario.ca in a Zoom interview.

Eastern wolves were classified under 'special concern' in the early 2000s both federally and provincially.

Following a 2015 recommendation by a national endangered wildlife committee, Ontario uplisted the species to 'threatened.'

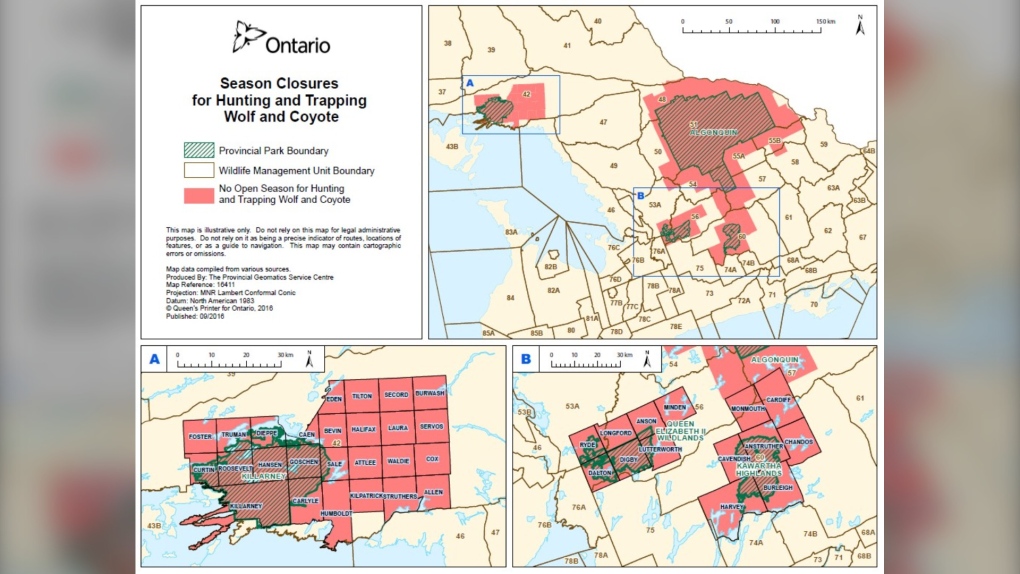

"So what the province has done is said 'OK, well, you can't hunt or trap in the parks anyway, but we'll make a doughnut of Crown land around these parks and wildland reserves and we'll restrict hunting for wolves and trapping the wolves in those areas in order to sort of tighten the level of control," Miller said.

Now, nine years later, Ottawa is following suit under its Species at Risk Act (SARA).

"ECCC’s decision to reclassify the Eastern Wolf as a threatened species is based on scientific advice it received from the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC)," Nicole Allen, a spokes person for the ministry told CTV News in an email.

"The timeline for listings depends on many factors including the extent of required consultations, the nature of the feedback received, and the scope of the socio-economic impact analysis. The listing for the eastern wolf was at the high end of the complexity range, requiring extended consultations with Indigenous communities and a detailed socio-economic analysis following the consultations."

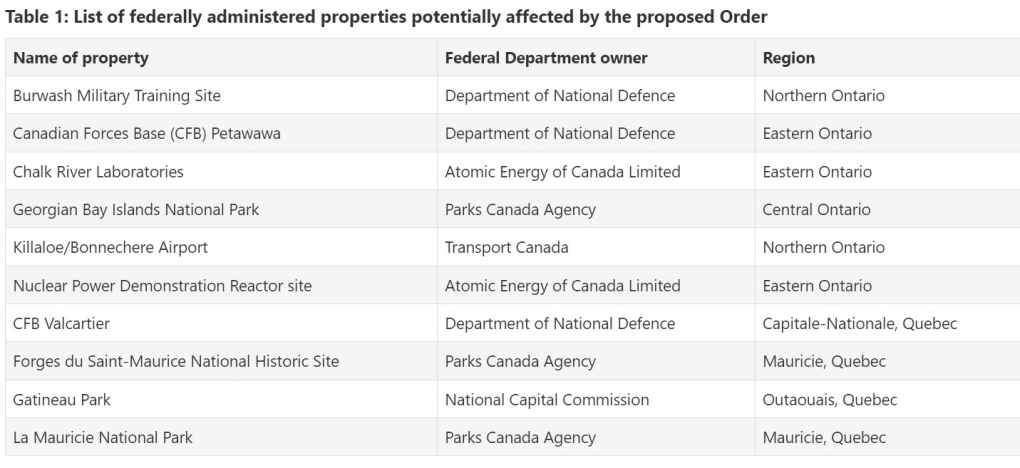

The move will affect the big military bases, chunks of federal land and national parks that weren't covered before.

"They hunt the moose and the deer and the beavers and smaller animals that they can get at, but, so they're critical in maintaining the structure of those wildlife communities," Miller said.

"We don't know how many are there, but we do know that those big tracts of land are useful (for) wolves to protect and expand their potential range."

While the new protection on federal land went into effect last month, trappers from the Ontario Fur Managers Federation oppose the move.

During the 30-day public comment period on the proposed amendment, the ministry said 385 of the 406 comments it received opposed the proposed order.

"I just can't believe that the federal government is going to move forward nine years later on data that is out of date without even looking at any of the new studies," Ray Gall, VP of the central region for Ontario Fur Managers Federation, told CTV News in a Zoom interview.

"The numbers just don’t add up with what the protectionists are saying and what is actually on the landscape."

He said he's been taking quite a few wolves off the land every year and hasn't seen a reduction in numbers.

"We're not looking to murder every animal on the landscape. All you need to do is take one animal, two animals perhaps out of a pack just to disrupt their activities," Gall said.

"It just gives the ungulates and the beavers and the other animals on the landscape just a bit of a fighting chance."

Since provincial protection was upgraded in 2016, Gall said the beaver harvest in the 40 townships surrounding Algonquin Provincial Park has been reduced by 40 per cent.

He said the fur managers want the restrictions lifted as soon as possible.

As stewards of the land, Gall said it is in the trappers' and hunters' best interest not to kill everything.

"We are highly regulated through the tools that we use. People may not agree or believe that trapping is an important management tool but it is," he said.

"If you over-harvest, next year you aren't going to have anything."

Meanwhile, Miller said the eastern wolf is not in danger of extinction and trapping will still be permitted on private land.

"Should further protections be required outside the range of federal lands, significant consultation would take place and relevant impacts would be considered before protections would be extended to non-federal lands," the ministry said.

The 2021 SARA management plan states "an effective population size of at least 500 mature individuals" is needed to sustain the genetic diversity required to ensure the viability of the eastern wolf population.

According to a 2016 study (Rutledge et al), a population of 2,500 to 4,545 wolves would be needed to reach the effective population size.

There is currently no recovery strategy for the eastern wolves.

"Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) is working on a recovery strategy to support the recovery efforts for the eastern wolf," the ministry said.

"The strategy will be written in collaboration with provincial governments, federal departments responsible for the federal lands where the eastern wolf is found as well as First Nations groups and Indigenous organizations. Landowners and others affected by the strategy will be consulted as part of the process."

In the 2021 management plan, a performance review will be performed every five years to assess the population's viability and ensure the extent of the species' range in Canada is maintained.

"The process for changing its status would begin with a reassessment by COSEWIC saying that its status has changed," the ministry said.

"If COSEWIC were to reassess the species at a different status, the listing process for amending Schedule 1 would then be undertaken again."

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Stunning photos show lava erupting from Hawaii's Kilauea volcano

One of the world's most active volcanoes spewed lava into the air for a second straight day on Tuesday.

Richard Perry, record producer behind 'You're So Vain' and other hits, dies at 82

Richard Perry, a hitmaking record producer with a flair for both standards and contemporary sounds whose many successes included Carly Simon’s 'You’re So Vain,' Rod Stewart’s 'The Great American Songbook' series and a Ringo Starr album featuring all four Beatles, died Tuesday. He was 82.

Read Trudeau's Christmas message

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau issued his Christmas message on Tuesday. Here is his message in full.

What is flagpoling? A new ban on the practice is starting to take effect

Immigration measures announced as part of Canada's border response to president-elect Donald Trump's 25 per cent tariff threat are starting to be implemented, beginning with a ban on what's known as 'flagpoling.'

Hong Kong police issue arrest warrants and bounties for six activists including two Canadians

Hong Kong police on Tuesday announced a fresh round of arrest warrants for six activists based overseas, with bounties set at $1 million Hong Kong dollars for information leading to their arrests.

Dismiss Trump taunts, expert says after 'churlish' social media posts about Canada

U.S. president-elect Donald Trump and those in his corner continue to send out strong messages about Canada.

Indigenous family faced discrimination in North Bay, Ont., when they were kicked off transit bus

Ontario's Human Rights Tribunal has awarded members of an Indigenous family in North Bay $15,000 each after it ruled they were victims of discrimination.

Heavy travel day starts with brief grounding of all American Airlines flights

American Airlines briefly grounded flights nationwide Tuesday because of a technical problem just as the Christmas travel season kicked into overdrive and winter weather threatened more potential problems for those planning to fly or drive.

King Charles III is set to focus on healthcare workers in his traditional Christmas message

King Charles III is expected to use his annual Christmas message to highlight health workers, at the end of a year in which both he and the Princess of Wales were diagnosed with cancer.